Delhi’s Air Crisis has once again drawn national attention after the Supreme Court strongly criticised the Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM). The court pointed out that CAQM has failed to clearly identify the main causes of worsening air quality in Delhi-NCR and has delayed the implementation of long-term solutions.

This criticism highlights a long-standing issue. Delhi’s Air Crisis no longer limited to a few winter months. It has become a year-round public health crisis that affects millions of people and demands permanent, preventive solutions instead of repeated emergency actions.

Supreme Court Raises Serious Concerns

The Supreme Court’s remarks reflect growing concern over the lack of effective planning. While authorities often announce short-term steps such as construction bans, traffic restrictions, and school closures, these measures offer only temporary relief.

The court emphasised that without identifying and addressing the root causes of pollution, air quality will continue to deteriorate. Among the many contributors, stubble burning and vehicle emissions remain two of the most significant and persistent sources of pollution in Delhi-NCR.

Stubble Burning: A Major Seasonal Contributor to Delhi’s Air Crisis

Every year after the harvest season, large amounts of crop residue are burned in neighbouring states. The smoke from this practice travels to Delhi-NCR and combines with local pollutants, sharply increasing particulate matter levels.

Farmers often burn stubble because it is the quickest and least expensive way to clear fields. Despite awareness campaigns and penalties, the practice continues because practical and affordable alternatives are limited.

Until agricultural waste is treated as a valuable resource. Rather than a disposal problem, stubble burning will remain a major contributor to Delhi’s air pollution.

Vehicle Emissions: A Daily Source of Pollution

Delhi has one of the highest numbers of vehicles in India. Petrol and diesel vehicles release harmful pollutants such as nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, and fine particulate matter every day.

Measures like the odd-even scheme and stricter emission norms help only for short periods. As long as fossil fuels dominate the transport sector, vehicle emissions will continue to harm air quality.

A real improvement requires cleaner fuels and a gradual shift away from fossil energy in transportation.

Why Short-Term Measures Keep Failing

Emergency actions are reactive by nature. They reduce pollution only after air quality has already worsened. Once restrictions lifts, pollution levels rise again.

The Supreme Court’s criticism underlines the need for preventive and long-term solutions that reduce pollution at its source. Clean energy plays a crucial role in achieving this shift.

Clean Energy as a Sustainable Answer for Delhi’s Air Crisis

Solutions for clean energy focus on preventing pollution rather than controlling it after the damage is done. By replacing fossil fuels with cleaner alternatives, emissions can be reduced across agriculture, transportation, and power generation.

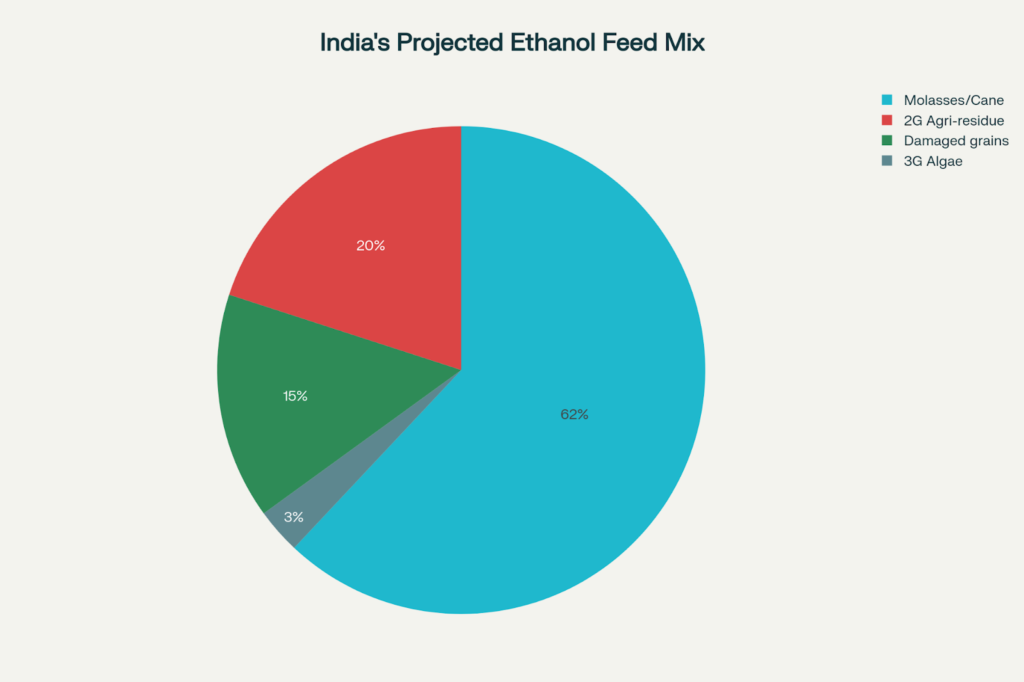

Among these alternatives, second-generation (2G) ethanol is particularly important because it addresses both stubble burning and vehicle emissions at the same time.

How 2G Ethanol Addresses Stubble Burning

2G ethanol is produced from agricultural waste such as rice straw, wheat straw, and other crop residues. Instead of burning this waste, it is collected and converted into clean fuel.

This gives farmers a financial incentive to sell crop residue instead of burning it. As a result, smoke emissions from fields are reduced, and agricultural waste becomes a source of value rather than pollution.

Cleaner Fuels for Cleaner Transport

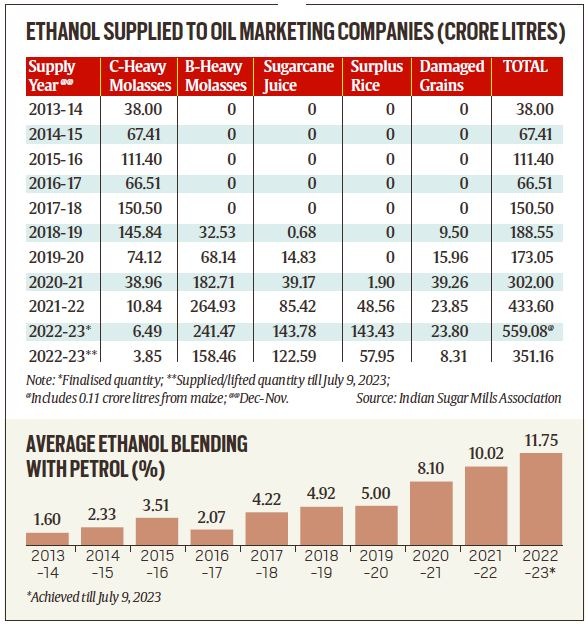

Ethanol blending in petrol helps reduce harmful emissions from vehicles. Ethanol burns cleaner than conventional fuels and lowers the release of pollutants that affect air quality.

As India increases its ethanol blending targets, the use of cleaner fuels can significantly reduce emissions from millions of vehicles. Since 2G ethanol does not compete with food crops, it supports sustainability without affecting food security.

Key Difference: Temporary Fixes vs Clean Energy Solutions

| Aspect | Temporary Measures | Clean Energy Solutions |

| Nature of action | Short-term and reactive | Long-term and preventive |

| Impact on pollution | Temporary reduction | Permanent reduction at source |

| Stubble burning | Not addressed | Converted into useful fuel |

| Vehicle emissions | Limited control | Reduced through cleaner fuels |

| Health benefits | Short-lived | Long-lasting improvement |

Khaitan Bio Energy’s Role in Reducing Pollution

Khaitan Bio Energy is contributing to India’s clean energy transition through the production of second-generation ethanol and advanced biofuels. Thus using patented technology, the company converts agricultural waste into clean energy.

This approach directly reduces pollution caused by crop residue burning while lowering dependence on fossil fuels. It also supports farmers by creating an additional income stream through biomass collection.

By focusing on scalable and sustainable solutions, Khaitan Bio Energy aligns environmental protection with economic and social development.

Clean Energy and Economic Growth Go Together

Clean energy is often seen as an expense, but it is actually an investment. Thus reduced pollution leads to lower healthcare costs, fewer pollution-related illnesses, and improved productivity.

Bioenergy projects create jobs in agriculture, logistics, and energy sectors, benefiting both rural and urban economies. Cleaner air also improves quality of life, especially for children and the elderly.

A Turning Point for India’s Air Quality Strategy

The Supreme Court’s warning should serve as a turning point. India cannot rely on emergency measures alone while ignoring the root causes of pollution.

By addressing stubble burning through bioenergy and reducing vehicle emissions through cleaner fuels, India can move toward lasting air quality improvement.

Conclusion

Delhi’s air crisis reflects deeper issues in energy use and waste management. So the Supreme Court’s criticism of CAQM highlights the urgent need for long-term solutions.

Clean energy—especially 2G ethanol—offers a practical way to tackle stubble burning and vehicle emissions together. Therefore by investing in such solutions, India can protect public health, support farmers, and ensure cleaner air for future generations.