India’s ethanol blending programme has become one of the most important pillars of the country’s clean energy transition. Over the past decade, the government has steadily increased the share of ethanol mixed with petrol, reducing crude oil imports while supporting farmers and rural industries.

The country’s Ethanol Blended Petrol (EBP) programme has progressed faster than expected. The original target was 20% ethanol blending (E20) by 2030, but policy acceleration moved the deadline forward to 2025–26.

Today, India is approaching that milestone. But a new question is emerging across policy circles and industry boardrooms:

What happens after E20?

The answer is becoming increasingly urgent as ethanol production capacity expands rapidly and new economic realities begin to shape the sector.

The Rise of India’s Ethanol Economy

India’s ethanol blending journey has been driven by three major goals: improving energy security, reducing carbon emissions, and strengthening the rural economy.

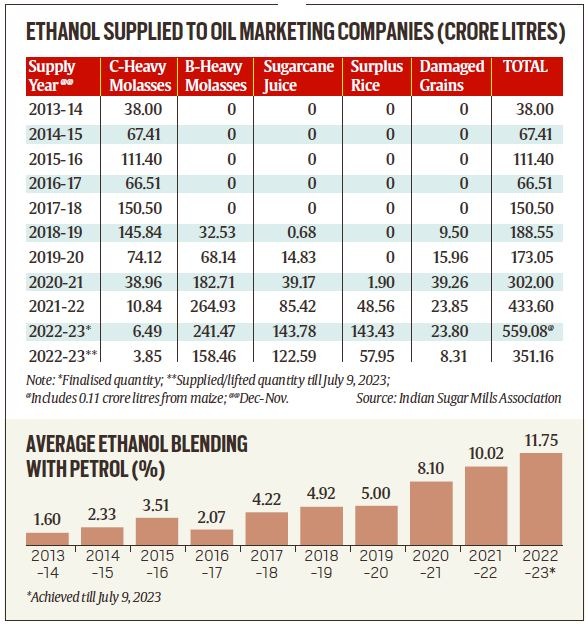

The progress has been remarkable. Ethanol blending in petrol has increased steadily over the years:

- Around 12% in 2022–23

- 14.6% in 2023–24

- Nearly 18% by early 2025

This rapid growth has transformed ethanol into a strategic component of India’s fuel mix.

At the same time, the programme has delivered economic benefits. The ethanol initiative has helped generate over ₹1.25 lakh crore in payments to farmers while also saving over ₹1.44 lakh crore in foreign exchange by reducing crude oil imports.

Such outcomes explain why ethanol blending is widely viewed as one of India’s most successful biofuel policies.

However, success has also created new complexities.

When Success Creates a New Problem

India’s ethanol sector has expanded aggressively over the past few years. Distilleries have been built across sugar-producing states, and grain-based ethanol plants have emerged rapidly.

But now, production capacity is beginning to outpace demand.

For the ethanol supply year 2025–26, producers have collectively offered 17,760 million litres of ethanol, while oil marketing companies require only around 10,500 million litres to meet the E20 blending requirement.

This gap between supply and demand highlights a structural challenge:

India may soon produce more ethanol than it can absorb under the current blending mandate.

Without new policy directions, several risks could emerge:

- Underutilised distillery capacity

- Reduced profitability for biofuel producers

- Slower innovation in advanced biofuels

Industry stakeholders therefore believe that India’s ethanol policy must now evolve beyond E20.

The Proposal for E27

One of the strongest proposals currently being discussed is increasing blending levels to 27% ethanol (E27).

Industry groups argue that the country already has sufficient capacity to support higher blending levels. According to the Indian Sugar and Bioenergy Manufacturers Association (ISMA), ethanol producers have invested more than ₹40,000 crore in building capacity and infrastructure.

Raising the blending limit could help absorb surplus ethanol while maintaining economic stability in the sector.

More importantly, a clear roadmap for higher blending could provide long-term confidence for investors and technology developers working in the biofuel ecosystem.

However, moving beyond E20 is not just a policy decision. It also requires technological readiness.

Vehicle engines, fuel infrastructure, and regulatory standards must evolve to accommodate higher ethanol concentrations.

The Emerging Role of Grain-Based Ethanol

Another major trend shaping the future of India’s ethanol sector is the rapid growth of grain-based ethanol production.

Out of roughly 400 ethanol manufacturing units in India, nearly 250 are now grain-based, using feedstocks such as maize and rice.

This shift reflects a broader diversification of feedstocks.

Earlier, the ethanol industry depended largely on sugarcane molasses. But fluctuating sugar output and water concerns pushed policymakers to encourage alternative sources such as grains and agricultural residues.

In fact, India has even used surplus rice stocks to support ethanol production when harvests were abundant, demonstrating how biofuels can help balance agricultural supply chains.

This diversification could become even more important in the coming years.

Beyond First-Generation Ethanol

As India looks beyond E20, the conversation is also expanding toward advanced biofuels.

Second-generation (2G) ethanol — produced from agricultural residues such as rice straw, wheat straw, and other biomass — is gaining attention as a long-term solution.

Unlike first-generation ethanol derived from food crops, 2G ethanol offers several environmental advantages:

- It uses agricultural waste rather than food grains.

- It helps reduce stubble burning, a major cause of air pollution in North India.

- It lowers lifecycle carbon emissions in the transport sector.

For India’s energy transition to remain sustainable, the next phase of ethanol expansion may need to rely increasingly on such technologies.

Policy Clarity Will Shape the Next Phase

India’s ethanol journey has been guided by strong government policy, including pricing support, tax incentives, and interest subvention schemes for distillery projects.

But as the country approaches the E20 milestone, the sector is now calling for the next phase of policy clarity.

Industry experts suggest that the government could consider several strategic steps:

- Defining blending targets beyond E20

- Promoting flex-fuel vehicles capable of running on higher ethanol blends

- Encouraging advanced biofuels such as 2G and 3G ethanol

- Expanding ethanol use in aviation fuels and green chemicals

These measures would ensure that India’s ethanol ecosystem continues to grow rather than plateau.

The Role of Innovation: Where Khaitan Bio Energy Fit In

The next stage of India’s ethanol roadmap will depend not only on blending targets but also on technological innovation.

Khaitan Bio Energy is exploring pathways that go beyond traditional ethanol production. Their focus on second-generation biofuels derived from biomass residues aligns closely with India’s long-term sustainability goals.

By converting agricultural waste into biofuels, such technologies can address two major challenges simultaneously: reducing pollution from crop burning and producing low-carbon transportation fuels.

In the “Beyond E20” era, innovations like these could play a crucial role in ensuring that ethanol remains a scalable and sustainable component of India’s clean energy strategy.

The Road Ahead

India’s ethanol blending programme has already reshaped the country’s fuel landscape.

From a modest beginning a decade ago, ethanol has become central to the nation’s efforts to reduce oil imports, support farmers, and cut transport emissions.

Yet the success of E20 marks not the end, but the beginning of a new phase.

Whether the future involves E27 blending, advanced biofuels, or entirely new applications of ethanol, the next chapter will depend on how quickly policy, technology, and industry evolve together.

One thing is clear:

India’s biofuel story is far from over — and the journey beyond E20 may be even more transformative.